American companies rushed to import goods from Asia in May, triggering record-setting export figures from Vietnam, Taiwan, and Thailand as they moved to beat a looming deadline for new U.S. tariffs proposed by President Donald Trump.

The surge in shipments—driven by fears of steep “reciprocal” tariffs that could take effect in early July—has upended normal seasonal trade patterns. Typically, U.S. imports from Asia peak later in the year in preparation for the holiday season. But this year, businesses front-loaded orders to avoid anticipated costs.

Vietnam and Thailand saw their exports to the U.S. jump 35% year-over-year in May, while exports from Taiwan skyrocketed nearly 90%, according to newly released trade data. South Korean shipments also hovered near record levels and appear to have risen again in early June.

These figures are expected to start appearing in official U.S. trade data this week, potentially complicating ongoing negotiations between Washington and several Asian economies over the size and scope of new tariffs.

The rush to import has widened the U.S. trade deficit significantly. Analysts estimate the May trade gap hit US$91 billion, pushing the 2025 year-to-date deficit to nearly US$643 billion—surpassing pandemic-era records. Although European pharmaceutical imports have also contributed to the widening gap, the bulk of the shortfall is being driven by Asia.

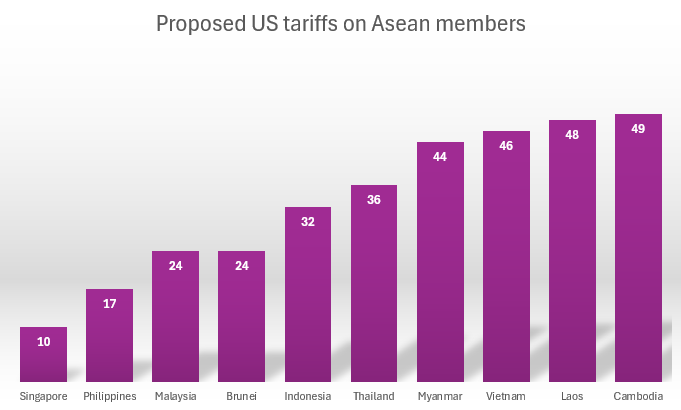

The current trade boom may be short-lived. If Trump follows through with plans to impose historically high tariffs on imports from Southeast Asian nations next month, the flow of goods could quickly slow, threatening economic momentum across the region.

Already, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group has downgraded its 2025 GDP growth forecast for its 21 member countries, lowering its projection from 3.3% to 2.6%, citing escalating trade tensions.

China is already feeling the impact. Despite a mid-May tariff truce agreed in Geneva, Chinese exports to the U.S. declined in May. High existing duties continue to pressure exporters, prompting some to reroute goods through third-party countries in a process known as “origin washing” to avoid tariffs.

Meanwhile, Chinese companies are increasingly turning to other international markets or focusing on domestic sales to offset falling U.S. demand. With China’s economy still grappling with weak consumer spending and a sluggish property sector, sustained export declines could add more strain.

Other Asian economies could soon face similar headwinds if they fail to reach agreements with the U.S. and avoid being swept up in the next round of tariff hikes. For now, the region’s exporters are racing against the clock.