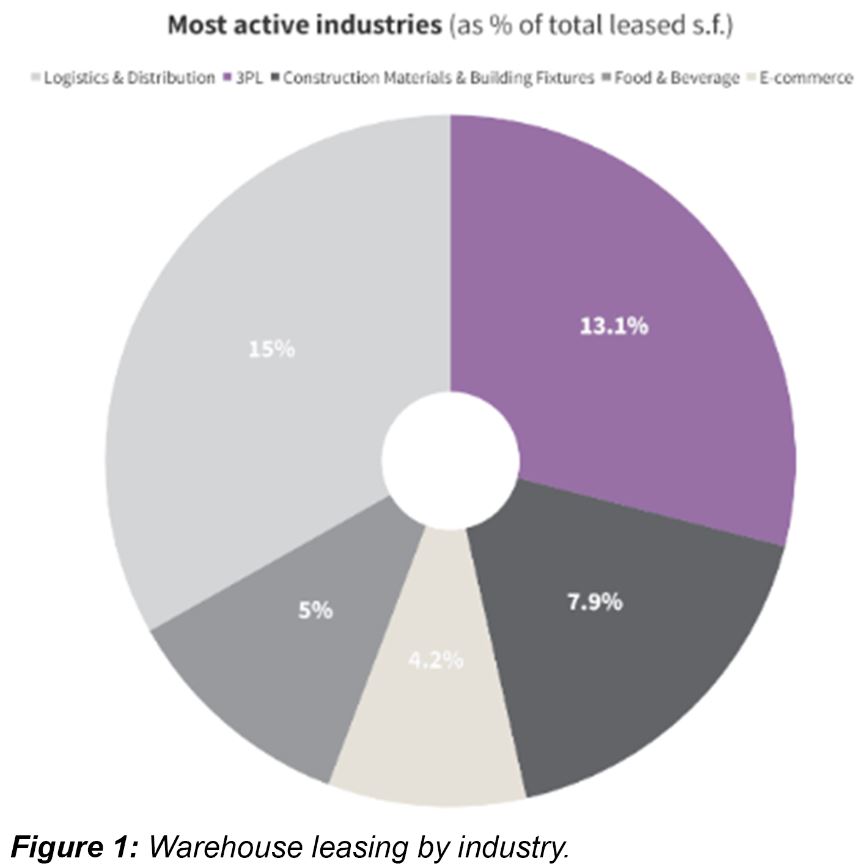

According to data from Industrial real-estate services firm JLL, logistics and distribution firms and 3PLs are the top takers of warehouse space in the U.S., accounting for 15% and 13.1% of the total area respectively (see Figure below).

The tightness in warehousing space for the 3PL industry in the U.S. has exponentially increased lease rates.

In some areas, it has tripled over the last three to four years and it’s getting increasingly difficult to find a warehouse facility that fits a CFS operation.

Almost everything being constructed currently is for e-commerce such as Amazon and the like, along with warehousing and distribution.

These developments are being built with little thought to requirement for the amount of doors needed as well as container and chassis parking,” observes Thorkild Hove, senior vice president, at ICT.

Elevated volumes, extended dwell times

Rising inflation and excess inventory levels have muted the demand for goods but U.S. ports are still struggling with congestion and a trade imbalance.

“Compared to the surge in 2021, inbound volumes into the U.S. have moderated but it continues to be relatively high with disproportionately more imports than exports,” notes Michael Tiernan, vice president of operations at ICT.

Import containers are not moving out of the ports at a fast enough rate that is needed to keep up with the amounts coming in off container vessels.

Data from FourKites shows import dwell times at U.S. West Coast Ports are at 7.8 days, -16% lower than the beginning of the year.

Congestion has shifted Eastward and dwell times on the East Coast are at 6 days, up 16% since the beginning of 2022 (see Figure below).

“Containers are dwelling on terminals longer while sitting on chassis which consequently keeps much-needed equipment out of circulation,” Mr. Tiernan points out.

Accumulating empty containers tie up chassis

The growth in imports through the U.S. East and Gulf Coast ports is adding to the number of empty containers accumulating at ports such as New York and New Jersey.

According to the Port of New York and New Jersey’s (PANYNJ) published data, loaded imports grew 36% in the first half of 2022 versus the same 2019 period, while exports fell -10%.

“There used to be about 60,000 empty shipping containers sitting up at the port on average. There are now over 200,000 empties which have built up around the port complex since January,” says Mr. Tiernan.

With empty containers lingering on chassis, it renders them non-operational for that duration.

Detention and demurrage fees

With container terminals overfilled with containers, truckers are not able to get access to shipments.

“Ocean carriers are charging shippers late fees for failing to pick up loaded containers and return empty boxes quickly enough.

The storage of containers is now being forced back on to shippers and drayage truckers,” warns Mr. Tiernan. “

A benchmark report by Container xChange found that detention and demurrage (D&D) charges imposed by container lines on U.S. shippers are the highest globally in 2022

Challenge of returning empty containers

Mr. Tiernan adds that inefficiencies in drayage operations are complicating the situation. “Not only is port access restricted by available appointments for slot capacity, but ocean carriers are also limiting where an empty container can be dropped off.

Thousands of truckers are all lining up to get the empties returned. That just creates so much more chaos and traffic. Not all truckers will be successful in returning the container even if they have secured an appointment.

When the port or the ocean carrier has reached their quota for containers being returned, truckers will be turned away. It can take four to eight days to get another return slot.”

The biggest challenge is the length of time it takes to make a move according to Mr. Tiernan.

“Typically, a driver can execute three to four container moves per day out of the port. Due to the various challenges and delays, efficiency has more than halved, to about one to one-and-a-half container moves per driver per day,” he explains

Shortage of draymen and drivers

The supply chain delays are not only about vessels delays and idling vessels in major ports and the huge influx of import containers piling up, points out Mr. Hove.

“It is also about shortage of draymen and drivers, as well as no manpower to customs clear the goods in time, the staff to find the less-than-truckload (LTL) truck power.

Even then, if they find it, the LTL truckers do not have the capacity. This has been going on since last year, but we do see some improvement in the flow of goods through our CFS’s.”